Binary Image Segmentation Using Synthetic Datasets

Binary Image Segmentation Using Synthetic Datasets

In computer vision, one of the most common challenges is to remove the background from the foreground of an image. A popular solution to this problem is to use a semantic segmentation model to separate the foreground from the rest of the image. There are several general-purpose models available that can solve the binary segmentation problem, such as U-Net, Dichotomous Image Segmentation (DIS), Mask R-CNN, and Fully Convolutional Networks.

However, in cases where you have a specific and unique domain, you may need to train your own model. The first step in doing so is to create a dataset. Traditionally, segmentation masks are created by hand using an image editor like GIMP. However, this process can be time-consuming and lead to a decrease in data quality.

To address this issue, we trained a segmentation model using a synthetic dataset that is scalable, iterative, and can be generated automatically. We found that on our very specific domain, our model performed better than U2Net and DIS. Additionally, our model was fast to train and can be easily improved in the future by adding more data.

Overall, our work demonstrates the effectiveness of synthetic datasets for training segmentation models in unique domains, and highlights the importance of automating dataset creation to save time and improve data quality.

Problem domain

In Biano, we have a very specific domain of home decor. This data is of various shapes and sizes, sometimes with white background which is preferable, but many times the product is situated in a scene. Often, there are other objects on the product. Many products contain thin shapes such as lamps or chairs which prove difficult to general purpose models. Some examples are here:

Product with white background are not so difficult.

Garden furniture is one of the hardest.

This scene is quite hard. What should we include into the foreground? Just the table and chairs, or also the decorations on the table?

The background and the strings make segmentation really difficult.

Up to now, we use a solution that incorporates the U2Net model since we also wanted from the model to determine the main object on the scene (such as in the case of the table with chairs scene). The model is impressive in many cases,

|

|

|

|

However, it fails in many others,

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Creation of Synthetic Dataset

As we said before, to create a representative dataset by manual creation of masks of data such as the chair swing with green plants in the background would prove very strenuous.

Previous Works

Synthetic dataset are not new, although there is not so much literature reference as one would expect. Some of the examples include

- Synthetic Data for Deep Learning (2019): A comprehensive review of synthetic data creation. They cover multiple areas such as creation of synthetic scenes, people, objects for scene awareness.

- Synthetically Trained Neural Networks for Learning Human-Readable Plans from Real-World Demonstrations (2018): This paper presents a method for training neural networks to learn human-readable plans from real-world demonstrations, using synthetic data to augment the training set. The authors show that the use of synthetic data improves the robustness and accuracy of the trained models.

- Learning from Synthetic Data: Addressing Domain Shift for Semantic Segmentation (2018): In this work, the data is synthesized by a features extraction using one network and generating them using another network. They train the data based on the GAN approach.

- Learning Semantic Segmentation from Synthetic Data: A Geometrically Guided Input-Output Adaptation Approach (2018): In this work, the authors face the same difficulty of how to obtain training segmentation data as we do. Their domain is the city scene. They create the synthetic data using 3D models.

- SynthSeg: Segmentation of brain MRI scans of any contrast and resolution without retraining (2023): This is a medical scan ML work. The authors address the lack of an automatic method to segment findings on the magnetic resonance scans by devising their own neural network trained also with the help of synthetic data.

- Synthetic Dataset Generation for Object-to-Model Deep Learning in Industrial Applications (2019): In this article, the authors encounter a similar problem as we do: for a special domain, you have to generate your own data. Theirs is an industrial domain of placing products on shelves in a warehouse. They solve it by generating data using 3D models obtained by photographing real-world objects from different angles.

To our best knowledge, all these works created synthetic objects from scratch, i.e. as artificial 3D models of a reality they wanted to model. None of the authors tried our approach, i.e. synthetic combination of real objects.

Methodology for Creating a Synthetic Dataset

Let’s dive into the process of creating a synthetic dataset. Although we will be using specific examples, the methodology can be applied to any domain.

Firstly, it is essential to get familiar with the dataset. In the Biano example, 85% of the data has a white background, while 15% of the data is in a scene or has a one-color background (which is rare). Some products have shadows, which can be of various shapes, depending on the direction of the light. Most of the time, the product is in the center of the image, and sometimes, it is in the golden-ratio position. Occasionally it is even shifted to the side and is no longer the dominant object in the image. There can be objects in front of the product, text with dimensions, or other information. Spending some hours or even days on this initial step is worth it.

Next, we need to obtain some segmented images from our dataset to begin with. We made some samples of around 60,000 data and applied the models we had on hand. Then we asked annotators if any of the models segmented the product well. Since many of our products have a white background, we used some simple mathematical models to filter out white color and the U2Net as well.

After that, we made some decisions on how to create the initial synthetic dataset. We decided that about 10% of our data would have a white background, 10% would have some empty rooms as the background, and 80% would have white noise as a background. We believed that white noise would be a good substitute for overcrowded images with multiple products. We deliberately sampled the background against the real distribution, as segmenting white-background images is much easier, so their representation is not as important.

Since the product appears in different parts of the image, we randomly shifted its position. Additionally, since many products have a shadow, we created shadows behind them, with shapes that are either the same shape as the product or an ellipse. The position and size of the shadows also vary. All these processes were decided randomly. Due to this variability, we were able to create multiple samples from one image (we tried up to 7 samples but did not test the limits). We also made sure that the whole product stayed inside the image.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Architecture

To begin with, our focus was on tuning the data, so we started with some simple segmentation models already implemented in PyTorch. We experimented with several architectures, and after trying out different models, we settled on the Feature Pyramid Network architecture, with EfficientNet B5 as a backbone and the Imagenet as the encoder weights. We found that this architecture provided the best performance for our specific use case.

Train, analyse, adjust, repeat

White noise model

Then train your first model and observe where it fails. In our case, we discovered that the white noise background did not generalize well. The model overfitted to the white noise. Consequently, we completely abandoned this approach. For future reference, we will refer to this model as the “white noise model”.

Small note on white noise and machine learning: note that machine learning models resize the images using jpeg compression which focuses on the contrast and not so much on the color of the image. So if you generate image with white noise background for a big image and THEN resize it, your white noise would blur.

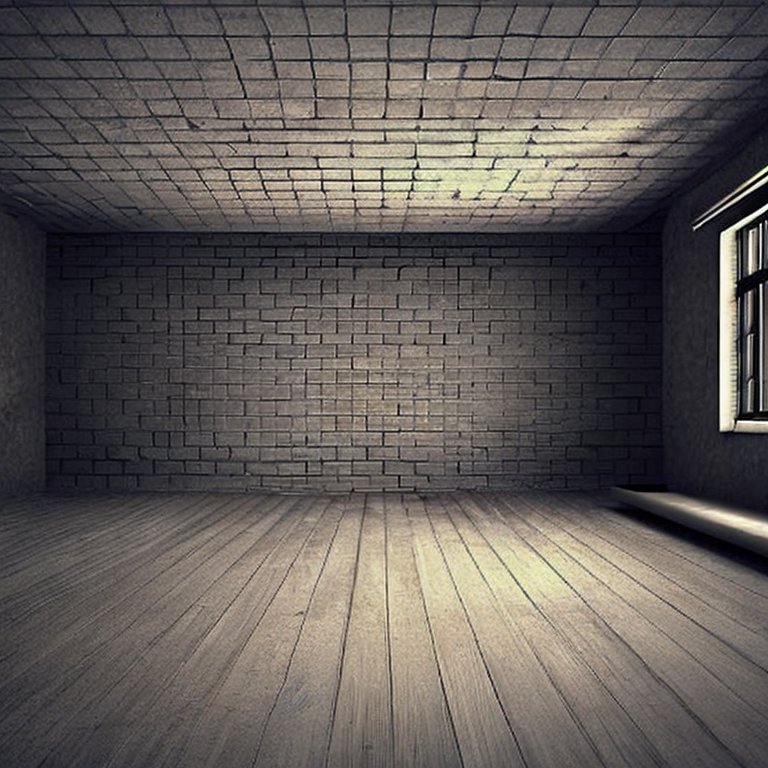

So, we iterated. We needed a couple of tens of empty room samples to replace the white noise. We used ChatGPT to create descriptions of the empty rooms which we prompted into Stable Diffusion that generated them. AI in real use.

The prompts looked like:

The room was completely empty, with no furniture or decorations to speak of.

The bare walls and floor gave the room a stark and desolate feeling.

The silence in the empty room was deafening, with no sounds to break the stillness.

To make the empty rooms more similar to the real data, we added some background products to them. The question was which products to add. The answer, as always in this research, was in the data. We analyzed some samples and picked some suitable categories from which to sample the background products (e.g. chairs, plants, tables, dressers). Their number, size, position, and choice were picked randomly. We did not generate a shadow for these background products and allowed them to move partially outside of boundaries of the image.

This model looked much more promising, but there were still some problems that might be possible to solve by a further improved dataset. We will call this model a “synthetic rooms model”.

Active learning model

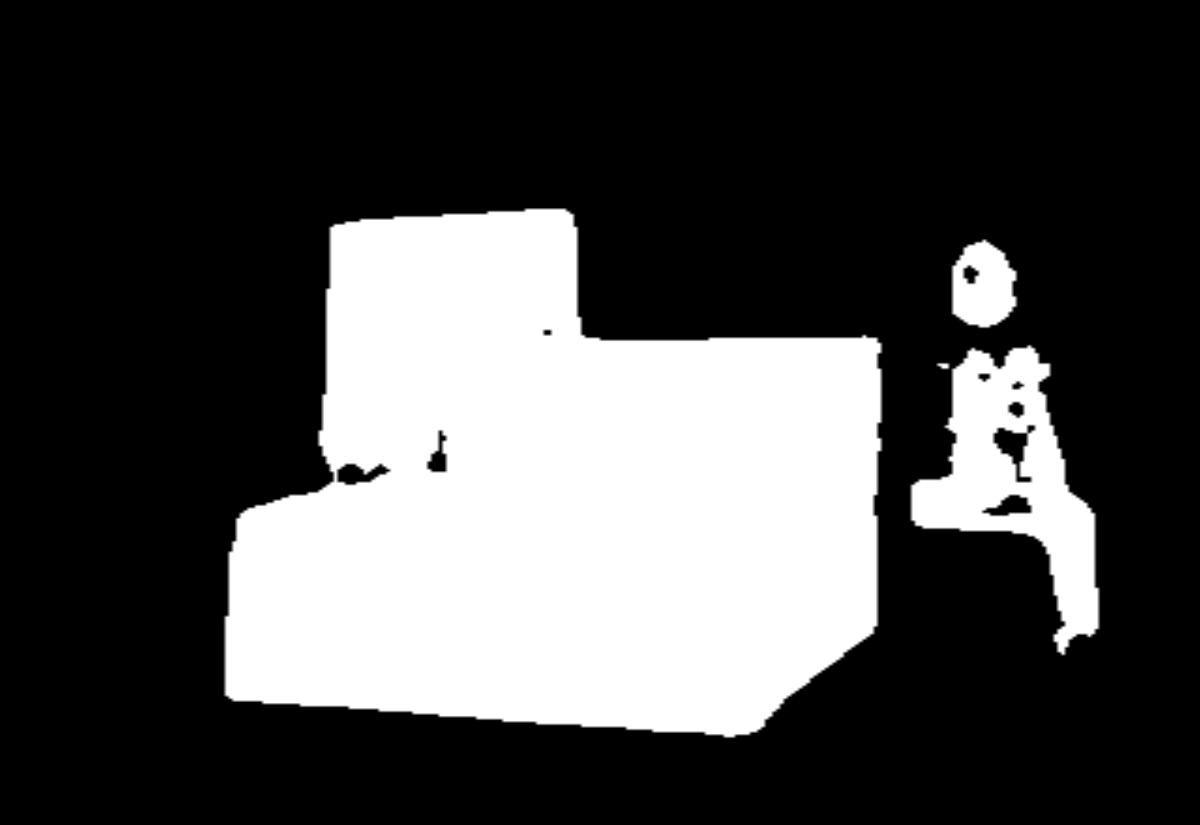

We picked up some random data (which were not in either of the train, validation or test sets, respectively) and inferred them with the synthetic rooms model and analysed where the model failed the most. We found that the worst results are for sofas, armchairs, beds and similar items placed in a room.

So we tried to add these data: we sampled the problematic categories, filtered out those data with white background, inferred them with U2Net and manually picked up those with a good U2Net mask. This gave us 2000 samples (around 5% of the original set).

Additionally, we put some products with background from the Biano data within the empty rooms “canvases” serving as backgrounds for the data. We trained models with both enhancements separately on a smaller dataset. After analysis of the data, we decided that both features made a difference and trained a big model with both of them. We will call this model “active learning model”.

We can see that although not perfect, the result is indeed improved.

Metrics

There are multiple metrics suitable for segmentation. We measured mean average precision, however, we relied most on SSIM metric original paper here, its use for binary image segmentation here which argue, that for capturing the fine details of the foreground image, this metric is the most suitable. However, we also evaluated the data with annotations.

Here we would like to stress out that segmentation metrics cannot cover the whole picture and some common sense evaluation is always recommendable, at least as a helping metric.

Test set

In machine learning, the best praxis is to have your test set at hand at the beginning of the project. However, creating a training data set for segmentation is difficult, so during the development of our experimental models, we relied on standard test set measurements and eye-measurements.

Just before training the active learning model, we created a test set of approximately 700 pieces of data that defined our test set. We sampled around 3 pieces from each category to reduce the effect of large categories. Out of the 700 pieces of data, around 500 could have been segmented using one of the models at hand (U2Net or our last experimental model), and we manually segmented 200 pieces in the GIMP image editor. Although the test set is small, the masks were of high quality. As a result, we were able to ensure that our models’ predictions were accurate and of high quality.

Results

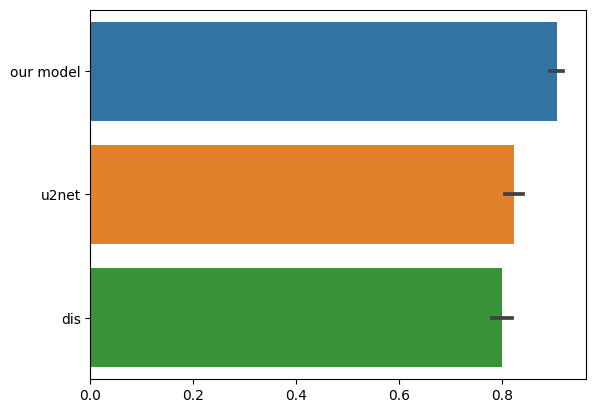

In this section, we will compare our last model with the U2Net and DIS models, where the latter is the state-of-the-art (SOTA) binary image segmentation model for difficult datasets.

Visually, the results of the final model appeared better than DIS in many cases, but worse in others.

For independent measurement, we used the SSIM metric, as mentioned earlier. We cropped the images respective to the ground truth masks to obtain a more precise measure of small objects with a large surrounding background.

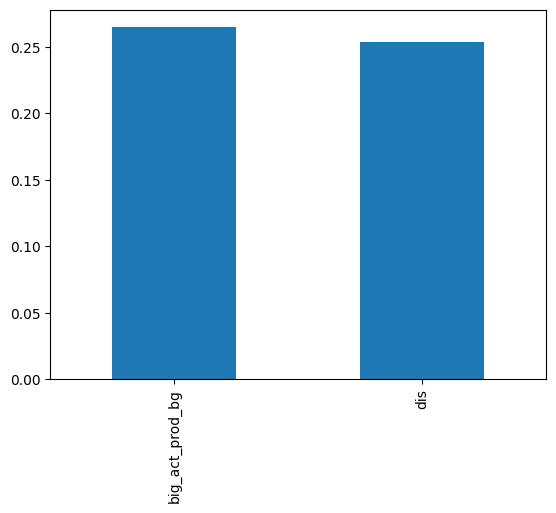

The mean accuracy of the compared models can be seen in the following figure:

Our model has a significantly higher mean accuracy than the U2Net and DIS models, as well as a higher SSIM metric, indicating better performance on our specific domain.

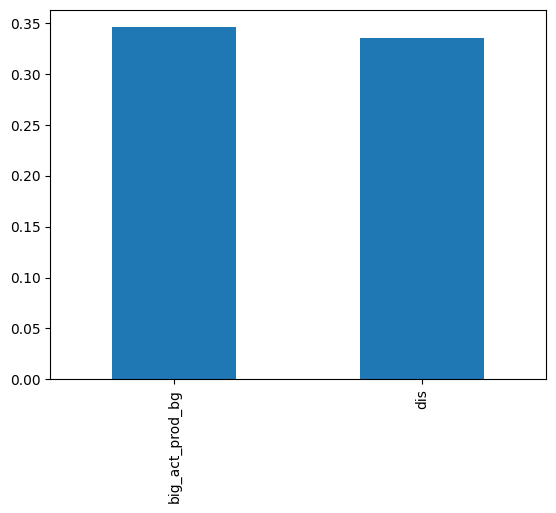

We also compared the performance of our model and DIS through manual annotations. We asked three annotators to select the masks that best segmented each image from our 700-piece test set. Each annotation was done three times, resulting in a total of 2100 annotations. We measured this metric in two ways:

- When at least two annotators agreed:

- Mention of the metric overall:

In both sub-metrics of the human measurement, our model performed better than the DIS model. However, it should be noted that the number of samples is too low for this kind of metric. Properly measuring this metric would require more scientific rigor, but we were satisfied enough with the results to not engage in further data splitting and training.

Conclusion

In this report, we demonstrated a method for constructing a synthetic dataset for training of segmentation models using sample data, pretrained models, and human annotations. By doing so, we were able to avoid the time-consuming and challenging task of manually creating masks.

We provided a detailed account of our methodology, with the dual purpose of documenting our project and inspiring other AI researchers and ML engineers who may be working on similar research.

Finally, we presented our results, which we are very pleased with. Our model was able to outperform the SOTA model DIS on our specific dataset, resulting in a more streamlined, precise, and lightweight model for production. All of this was made possible through meticulous data handling.